Summary

A persistent misconception circulates in compliance circles: organisations using AI systems to process personal data must obtain explicit individual consent from every person whose data they process. The claim sounds perfectly plausible given AI’s complexity and the heightened regulatory scrutiny. Upon closer examination, though, it doesn’t quite hold up.

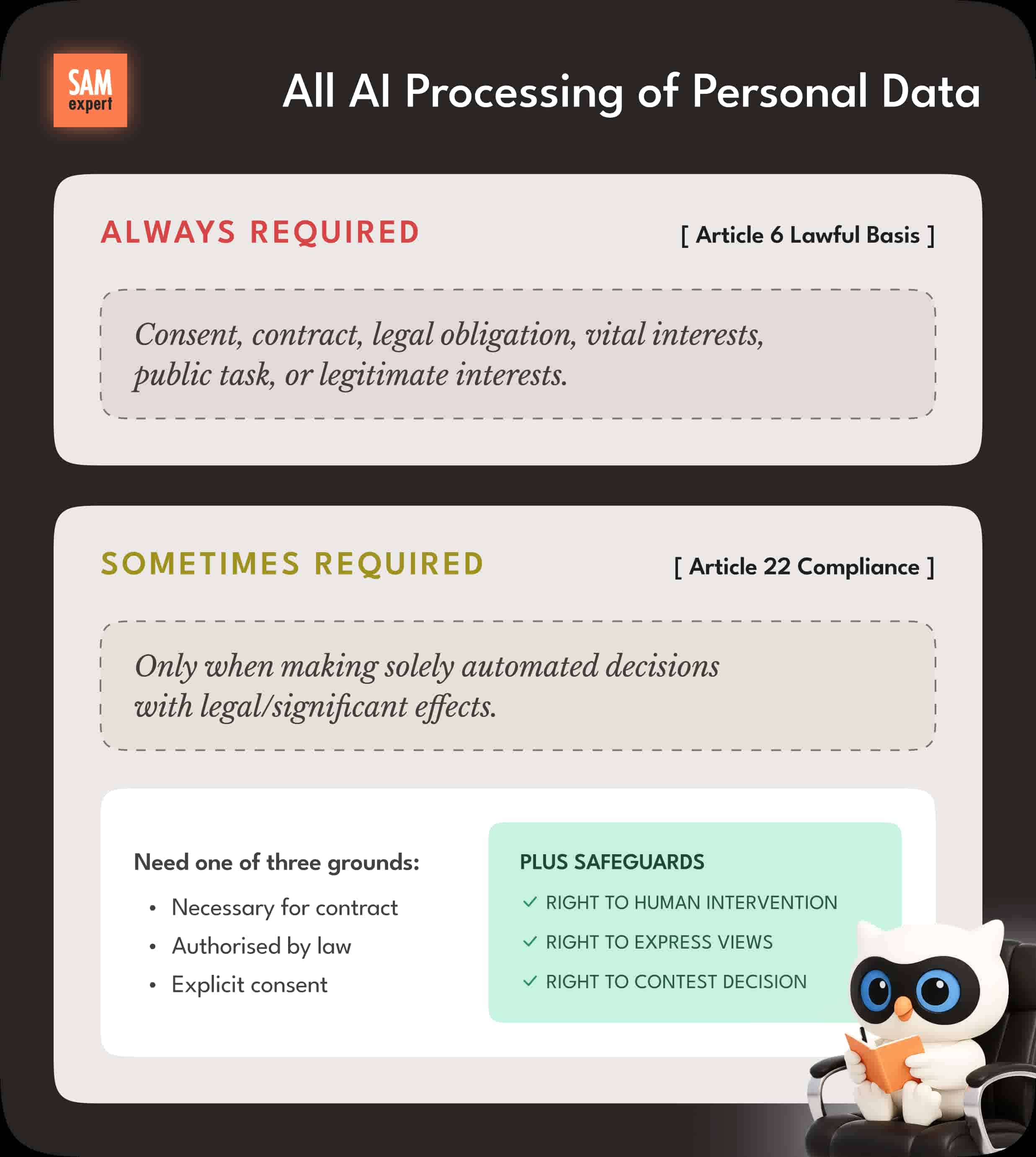

Understanding why requires examining what GDPR and the EU AI Act actually say about lawful bases for processing personal data, and recognising the critical distinction between processing data and making automated decisions.

GDPR’s Six Lawful Bases

GDPR Article 6 establishes six lawful bases for processing personal data. Organisations need at least one of these bases – not all six, and not specifically consent:

Consent — the data subject has given consent for specific purposes

Contract — processing is necessary for a contract with the data subject

Legal obligation — processing is necessary to comply with the law

Vital interests — processing is necessary to protect someone’s life

Public task — processing is necessary for a task in the public interest

Legitimate interests — processing is necessary for legitimate interests (except where overridden by the data subject’s rights)

The technology used for processing – whether manual processes, traditional software, or AI systems – does not determine which lawful basis applies. What matters is the purpose of the processing, the relationship with the data subject, and the context.

Practical Examples

An employer using AI to process payroll data relies on contract or legal obligation, not consent. A bank using AI for fraud detection relies on legitimate interests. A healthcare provider using AI diagnostic tools relies on contract or legal obligation (depending on jurisdiction). A recruitment platform using AI to match candidates with opportunities relies on contract when providing services candidates requested.

Consent is just one option. In many business contexts, consent is actually the weakest lawful basis because it can be withdrawn at any time.

Two Separate Questions: Processing Data vs Making Decisions

A fundamental source of confusion stems from conflating two distinct legal frameworks. Understanding the difference is essential.

Question 1: Do You Have a Lawful Basis to Process Personal Data?

Framework: GDPR Article 6 (or Article 9 for special categories)

The question applies to every processing activity involving personal data, regardless of technology. Whether you’re using paper files, Excel spreadsheets, traditional databases, or AI systems, you need a lawful basis under Article 6.

Examples of processing activities: - Storing customer email addresses in a CRM - Analysing employee performance metrics - Training an AI model on historical data - Running algorithms to classify documents - Generating personalised recommendations - Processing applications through any system

The requirement: Identify one of the six lawful bases (consent, contract, legal obligation, vital interests, public task, or legitimate interests).

AI doesn’t change the rules. Using AI to analyse data, make predictions, or generate outputs requires a lawful basis for that processing. AI doesn’t change which lawful bases are available.

Question 2: Are You Making Automated Decisions That Require Additional Safeguards?

Framework: GDPR Article 22

The question is separate and only applies when you’re making decisions that meet all three criteria: 1. Solely automated (no meaningful human involvement) 2. Producing a decision (not just processing, analysis, or recommendations) 3. With legal or similarly significant effects

Article 22 is not about processing data. Article 22 restricts certain types of decision-making.

Think of Article 22 as an additional layer of protection that sits on top of the Article 6 framework. You always need a lawful basis under Article 6. If you’re also making solely automated decisions with significant effects, Article 22 imposes additional restrictions.

The Relationship Between These Frameworks

Scenario 1: AI Processing Without Automated Decisions

Your company uses AI to analyse customer purchase patterns and generate marketing insights.

Article 6 question: Do you have a lawful basis to process customer data? (Probably legitimate interests after balancing test)

Article 22 question: Are you making automated decisions about individuals? (No – you’re generating insights, not making decisions about specific people)

Conclusion: You need a lawful basis under Article 6. Article 22 doesn’t apply.

Scenario 2: AI Making Recommendations That Humans Review

Your recruitment system uses AI to score CVs and recommend candidates. HR managers review the recommendations alongside other information and make hiring decisions.

Article 6 question: Do you have a lawful basis to process applicant data? (Probably contract or legitimate interests)

Article 22 question: Are decisions solely automated? (No – humans make the final decisions with meaningful oversight)

Conclusion: You need a lawful basis under Article 6. Article 22 doesn’t apply because humans are meaningfully involved.

Scenario 3: Solely Automated Decisions With Significant Effects

Your system automatically rejects loan applications below a certain AI-generated credit score without human review.

Article 6 question: Do you have a lawful basis to process applicant data? (Probably contract or legitimate interests)

Article 22 question: Are decisions solely automated with significant effects? (Yes – automatic rejection without human involvement affects access to credit)

Conclusion: You need both a lawful basis under Article 6 and compliance with Article 22’s restrictions. Article 22 requires one of three grounds: necessary for contract, authorised by law, or explicit consent. You must also implement safeguards including the right to human intervention.

Why the Distinction Matters

Processing personal data with AI ≠ Making automated decisions about people

You can process enormous amounts of personal data with AI without triggering Article 22. You can train models, generate insights, make predictions, classify information, and support human decision-making. Article 22 restrictions don’t apply to any of these activities.

Article 22 only restricts a specific subset of activities: solely automated decisions with legal or similarly significant effects on individuals.

Common Misconception Deconstructed

❌ Wrong thinking: - “We use AI” → “AI makes automated decisions” → “Article 22 applies” → “We need explicit consent”

✅ Correct thinking: 1. “We process personal data” → “We need a lawful basis under Article 6” → “Let’s identify the appropriate one (often contract or legitimate interests)” 2. Separately: “Do we make solely automated decisions with significant effects?” → If yes: “Article 22 applies, we need one of its three grounds plus safeguards” → If no: “Article 22 doesn’t apply”

Most AI use cases need to answer Question 1 (lawful basis for processing). Far fewer need to address Question 2 (Article 22 restrictions). Conflating these questions leads to the false conclusion that AI requires consent.

A Visual Framework

The distinction clarifies why the claim about universal consent requirements doesn’t quite reflect the regulatory framework. Processing personal data with AI requires a lawful basis. Consent is just one option. Making certain types of automated decisions triggers additional requirements. Even then, consent is only one of three available grounds.

The AI Act’s Explicit Position

The EU AI Act (Regulation 2024/1689) entered into force in August 2024. One might reasonably assume the AI Act creates new consent requirements for AI processing — though this isn’t quite the case.

Recital 63 states explicitly:

“This Regulation should not be understood as providing for the legal ground for processing of personal data, including special categories of personal data, where relevant, unless it is specifically otherwise provided for in this Regulation.”

The AI Act does not create new legal grounds for processing personal data. The regulation defers to GDPR’s existing framework. When AI systems process personal data, organisations must identify an appropriate lawful basis under GDPR Article 6 - but nothing about using AI changes which bases are available or appropriate.

Recital 69 reinforces the point:

“The right to privacy and to protection of personal data must be guaranteed throughout the entire lifecycle of the AI system. In this regard, the principles of data minimisation and data protection by design and by default, as set out in Union data protection law, are applicable when personal data are processed.”

The AI Act requires organisations to follow GDPR principles when processing personal data through AI systems. The regulation does not replace those principles with blanket consent requirements.

Limited AI Act Consent Requirements

The AI Act does create specific consent requirements in narrowly defined circumstances:

Article 61 requires informed consent when individuals participate in real-world testing of high-risk AI systems outside regulatory sandboxes. The requirement applies to AI developers and vendors testing their systems before market launch. It does not apply to organisations using already-deployed AI systems.

Recital 141 makes an essential distinction:

“Consent of subjects to participate in such testing under this Regulation is distinct from, and without prejudice to, consent of data subjects for the processing of their personal data under the relevant data protection law.”

The AI Act’s testing consent is separate from GDPR consent. Organisations testing high-risk AI systems need both: consent to participate in testing (AI Act requirement) and an appropriate lawful basis for processing personal data (GDPR requirement, which might be consent but doesn’t have to be).

What “Testing” Means

Real-world testing under Article 60 refers to AI developers testing their products on real people in real-world situations before commercial launch. Examples include:

A company developing medical diagnosis AI testing it in actual hospitals with real patients

An AI recruitment system being tested with real job applications

A facial recognition system being tested in public spaces

The testing provisions do not apply to: - Using already-launched AI systems in your business (like using ChatGPT, Copilot, or any deployed AI tool) - Processing data through operational AI systems - Normal business operations with AI

For most businesses using AI systems (rather than developing them), Articles 60-61 don’t apply at all.

Understanding Article 22: When Does It Apply?

Much of the misconception about AI requiring consent likely stems from GDPR Article 22, which addresses automated decision-making and profiling.

Article 22(1) gives individuals the right not to be subject to decisions based solely on automated processing which produce legal effects or similarly significant effects. The provision lists three exceptions where such processing is permitted:

Necessary for entering into or performing a contract

Authorised by Union or Member State law

Based on explicit consent

Someone reading quickly might conclude: “AI equals automated decisions, automated decisions need consent, therefore AI needs consent.” This reasoning doesn’t quite stand up to examination.

What Article 22 Actually Covers

Article 22 applies only when all these elements are present:

Solely automated processing (no meaningful human involvement)

Producing a decision (not just a recommendation or analysis)

With legal or similarly significant effects on the individual

Most AI use cases do not meet all three criteria. AI systems often provide recommendations that humans review before making decisions. Many AI applications perform analysis or classification without producing decisions that significantly affect individuals. Even when AI does make automated decisions with significant effects, contract performance and legitimate interests (subject to safeguards) often provide appropriate legal grounds.

Real-World Article 22 Scenarios

Recital 71 provides examples: automatic refusal of online credit applications or e-recruiting practices without human intervention. Additional scenarios that could trigger Article 22 include:

Recruitment and hiring: AI automatically rejecting job applications without human review affects access to employment opportunities. However, AI scoring CVs for human recruiters to review does not trigger Article 22 because the human makes the final decision.

Credit and financial services: AI autonomously approving or rejecting loan applications without human oversight produces legal effects. AI providing credit risk assessments that loan officers review alongside other information does not trigger Article 22.

Healthcare: AI automatically denying insurance coverage or autonomously triaging patients creates significant effects. AI providing diagnostic support for clinicians who make treatment decisions does not.

Dynamic pricing: Automated systems showing different prices to different people based on profiling could trigger Article 22 if the pricing effectively bars access to services.

Employment management: AI automatically issuing disciplinary warnings based on attendance monitoring or autonomously adjusting pay based on productivity tracking without management review could trigger Article 22.

The “Meaningful Human Review” Requirement

The critical factor is meaningful human involvement. Having someone simply confirm AI outputs may not quite satisfy Article 22’s requirements. The human reviewer must have:

Authority to override the AI

Access to relevant information beyond the AI’s output

Genuine capacity to disagree with AI recommendations

Training and instructions on when not to follow AI recommendations

A human merely confirming AI recommendations without independent consideration may not sufficiently prevent Article 22 from applying. The human involvement must be active, not a token gesture.

What Article 22 Doesn’t Cover

Article 22 does not apply to:

Decisions made FOR you (as your agent): An AI booking flights or making purchases on your behalf is acting as your agent, not making decisions ABOUT you. The legal issues are addressed through contract law and agency principles, not Article 22.

Processing without decision-making: AI analysing data, generating insights, making predictions, or classifying information without producing decisions about individuals doesn’t trigger Article 22.

Recommendations that humans review: AI suggesting candidates, flagging risks, or ranking options for human decision-makers doesn’t trigger Article 22 if humans make the final decisions with meaningful oversight.

Special Categories of Personal Data

GDPR Article 9 imposes stricter requirements for processing special categories of personal data (health data, biometric data, racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious beliefs, trade union membership, genetic data, or data concerning sex life or sexual orientation).

Article 9(1) prohibits processing special categories unless one of the conditions in Article 9(2) applies. Explicit consent is one such condition — but there are nine others, including:

Processing necessary for employment, social security, or social protection law

Processing necessary to protect vital interests where the data subject is incapable of giving consent

Processing necessary for health or social care purposes

Processing necessary for public health purposes

Processing necessary for archiving, research, or statistical purposes

Many high-risk AI systems process special categories of personal data. The stricter requirements under Article 9 often apply. However, explicit consent remains just one option among several lawful conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: If I use ChatGPT or similar AI tools to process customer data, do I need explicit consent from those customers?

No. You need a lawful basis under GDPR Article 6 (probably legitimate interests or contract), but explicit consent is not required simply because you’re using AI tools. Your obligations depend on what data you’re processing, why you’re processing it, and your relationship with the data subjects — not on the fact that AI is involved.

However, you must ensure your use of third-party AI tools complies with GDPR’s requirements for processors, including appropriate data processing agreements and ensuring adequate safeguards.

Q: We’re using AI to screen job applications. Does Article 22 apply?

Article 22 applies if the AI automatically rejects applications without human review, AND the rejection significantly affects access to employment

Article 22 does NOT apply if: - AI scores or ranks applications but humans review the results and make hiring decisions with genuine discretion - Humans can and do override AI recommendations when appropriate

The human involvement must be meaningful — not just rubber-stamping AI outputs.

Q: Does the AI Act change the rules about consent?

No. The AI Act explicitly states (Recital 63) that it does not create new legal grounds for processing personal data. GDPR’s six lawful bases continue to apply unchanged. The AI Act’s only consent requirement relates to participating in testing of high-risk AI systems before market launch — and even that consent is separate from GDPR consent for processing personal data.

Q: Our AI system processes health data. Do we need explicit consent?

Not necessarily. Health data is a special category under GDPR Article 9, which has stricter requirements. Explicit consent is one option, but there are others including: - Processing necessary for health or social care purposes - Processing necessary for public health purposes - Processing necessary for preventive or occupational medicine

The appropriate lawful condition depends on your specific circumstances, not on whether you’re using AI.

Q: If someone opts out of automated decision-making under Article 22, can we still process their data?

Yes. Article 22 gives individuals rights regarding solely automated decisions with significant effects. Opting out of such decisions doesn’t prevent you from processing their personal data for other purposes (provided you have an appropriate lawful basis under Article 6).

For example, someone might object to automated credit decisions but you can still process their data to allow a human to make the credit decision.

Q: We use AI for fraud detection. What’s our lawful basis?

Fraud detection typically relies on legitimate interests (Article 6(1)(f)). You must conduct and document a balancing test showing that your legitimate interest in preventing fraud is not overridden by individuals’ rights and freedoms. You must also implement appropriate safeguards and provide transparency to data subjects.

Consent would be inappropriate for fraud detection because fraudsters wouldn’t consent, and requiring consent would undermine the purpose.

Q: Do cookie consent requirements apply to AI?

Cookie consent (under ePrivacy Directive/regulations) is separate from GDPR consent for processing personal data. If your website uses cookies or similar technologies for AI purposes, you typically need cookie consent. However, the AI processing itself requires a lawful basis under GDPR Article 6, which doesn’t have to be consent.

The confusion between cookie consent and GDPR lawful bases for AI processing is common but perhaps not entirely accurate.

Q: We want to train an AI model using customer data. Do we need consent?

Not necessarily. Training AI models is a processing activity that requires a lawful basis under Article 6. Many organisations rely on legitimate interests for model training, provided they: - Conduct and document a balancing test - Implement appropriate safeguards - Provide transparency to data subjects - Ensure compatibility with the original purpose for which data was collected - Consider data minimisation and anonymisation where possible.

The appropriate lawful basis depends on your specific circumstances, the nature of the data, and the purpose of the model.

Q: What if our AI makes a mistake? Does that affect our lawful basis?

No. The accuracy of AI outputs doesn’t particularly affect which lawful basis applies for processing personal data. However, GDPR’s accuracy principle requires you to take reasonable steps to ensure personal data is accurate. If your AI makes decisions based on inaccurate data, you could find yourself in breach of the accuracy principle regardless of your lawful basis.

For Article 22 decisions, you must also implement safeguards including the right for individuals to challenge decisions.

Q: Can we use consent as our lawful basis for AI processing?

You can, but consent is often not the best choice because: - Individuals can withdraw consent at any time, which may disrupt your processing - Consent must be freely given, which is difficult to demonstrate in employment or other imbalanced relationships - Consent requires clear, specific information about the processing - You must be able to demonstrate that valid consent was obtained

Contract, legal obligation, or legitimate interests are often more appropriate and stable lawful bases for business use of AI.

Q: Does using AI increase our GDPR obligations?

Using AI doesn’t create new obligations, but it may make certain existing obligations more relevant: - Data Protection Impact Assessments are often required for AI processing - Transparency obligations may be more complex when explaining AI processing - Article 22 safeguards apply if you make solely automated decisions with significant effects - The accuracy principle requires attention when AI makes or influences decisions - Security measures must address AI-specific risks

The fundamental framework remains the same: identify appropriate lawful bases, implement necessary safeguards, ensure transparency, and enable individuals to exercise their rights.

Legislative References

The following legislation governs this area:

GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation):

GDPR Article 6 - Lawfulness of processing

GDPR Article 9 - Processing of special categories of personal data

GDPR Article 22 - Automated individual decision-making

EU AI Act:

EU AI Act - Official text

AI Act Recital 63 - Confirms AI Act doesn’t create legal grounds for processing

AI Act Recital 69 - GDPR principles apply to AI

AI Act Recital 141 - Testing consent vs GDPR consent

AI Act Article 60 - Testing in real-world conditions

AI Act Article 61 - Testing consent requirements

AI Act Explorer - Browse the full AI Act

Additional Resources: ICO Guidance on AI and Data Protection | EDPB Guidelines on Automated Decision-Making

So What Does This Actually Mean?

The claim that organisations need explicit consent from everyone whose data they process with AI doesn’t quite hold water. The regulation provides six lawful bases. Consent is one option, not the only option.

The confusion stems from conflating two separate questions.

First: do you have a lawful basis to process personal data (Article 6)? Second: are you making solely automated decisions with significant effects that trigger additional restrictions (Article 22)?

Most AI processing only needs to address the first question. Even when Article 22 applies, consent remains just one of three available grounds.

The AI Act explicitly confirms it doesn’t create new legal grounds for processing personal data. Using AI doesn’t automatically trigger consent requirements. The same GDPR framework applies whether you’re using spreadsheets or neural networks.

The regulatory framework is complex, and confusion is understandable. That said, the complexity rather heightens the importance of getting the details right. The legislation is publicly available and, whilst complex in detail, rather clear on the core question. Organisations using AI should identify appropriate lawful bases, implement necessary safeguards, ensure transparency, and enable individuals to exercise their rights. The same principles apply whether you’re using spreadsheets or neural networks.

🖐 Ensure audit resilience and regulatory clarity. Learn more: Microsoft Audit Defense.

About this article: This analysis is based on GDPR (Regulation 2016/679) and the EU AI Act (Regulation 2024/1689) as they stood in November 2024. Organisations should consult qualified legal professionals for advice on specific situations. The legislative links provided are to official and authoritative sources.